Cet article fait partie d’un cycle

In 2013, the International Film Festival of La Roche-sur-Yon, (a nice town in Western France close by the ocean, co-directed at the time by Yannick Reix and Emmanuel Burdeau) wished to have Richard Linklater as its guest of honor. To seduce the director into accepting the invitation, Emmanuel Burdeau flew to Athens at the end of May. Linklater was there to attend the premiere of his last film, shot in Greece: Before Midnight. They talked a whole night in the hotel bar, recounting the journey of a work that, oddly enough, remains yet to be discovered by a wider audience. The rest is history: on the following fall, Linklater could not make it to La Roche as he was still working on the post-production of Boyhood, which would bring an international recognition that had been too long waited for. This is still the first part of this interview.

UNIVERSITY / BASEBALL

Emmanuel Burdeau : Are you originally from Austin ?

Richard Linklater : No. No one is from Austin ; you move there. I am from a little town in East Essex – Huntsville. It’s where the state prison is. They execute people. It’s pretty bad. Did you see my movie Bernie ? It’s like that.

So you actually knew a guy who was like Bernie ?

R. L. : Yes. My mom was a teacher at university. Huntsville is a very conservative little town. People are very friendly on the surface, but there is a dark undercurrent of bigotry and racism. Everything is good unless you’re gay or Black.

Did you study cinema ?

R. L. : Not academically. I took two classes: film history and film appreciation, at a community college. I majored in English because I wanted to become a writer. I also studied theater. I only went to college two years. I wanted to be a pro baseball player and a novelist – I failed at both. But I had that heart condition and I couldn’t run anymore. So I couldn’t play baseball anymore. At that point I was writing plays. I was kind of studying theater a little bit, just for a little while. Then I discovered cinema and I realized that was how I was thinking. It was like 30 years ago.

I wanted to be a pro baseball player and a novelist – I failed at both.

Did you actually work on stage, as an actor ?

R. L. : No, it was just in college – I did write plays, but not professionally.

Who were the writers you looked up to at that time ?R. L. : I went through a big Philip Roth phase. I took many years off that phase, but I recently started reading a lot of Philip Roth again. His latest books are quite wonderful – the last ten years. They’re small but they’re all kind of great. I mostly liked the classics, Russian, French.

They’re also a tradition in the US of writers writing about sports, which we don’t have in France. Such a thing as « baseball novels » even does exist.

R. L. : Yes, Don De Lillo for example. It’s a part of our culture which is both high-brow and low-brow. You could actually incorporate it into something serious. I don’t think Philip Roth ever did. But even Jack Kerouac invented a baseball game, very intricate, with cards – he was a huge baseball fan. Baseball is an impenatrable game, and there’s just so many cultures who don’t have it. It makes no sense for those cultures.

When you were playing baseball, you were playing at a special role ?

R. L. : There’s nine positions, so… In college, I was an outfielder, which means you’re far away from the play.

What was your strong point ?

R. L. : I was very fast. So getting on base, stealing bases, foreign runs… Make things happen.

Did your heart condition force you to stop all kind of sports ?

R. L. : Yes, I couldn’t run. I would get like headache. It began right at the beginning of my second season, so I didn’t have much of a career at all in college. But it was a good experience. It’s a fun way to go to college, because you’re treated like you’re kind of a star. It’s like being in a band or something. But even then, my mind was thinking of theater and writing. I was less into it. Ultimately I didn’t have the mentality to be a sport athlete. I thought too much. The best athletes don’t think that much ; they’re not that smart.

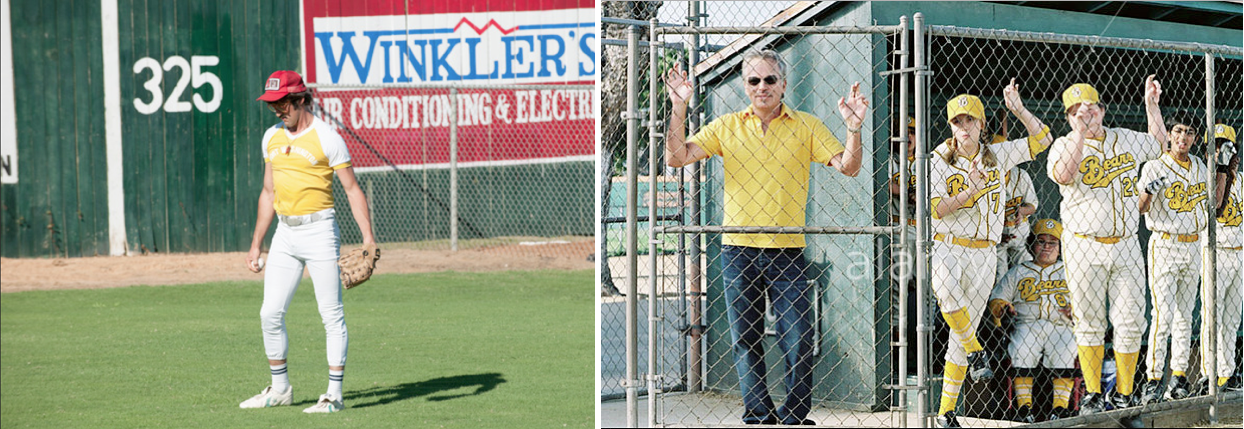

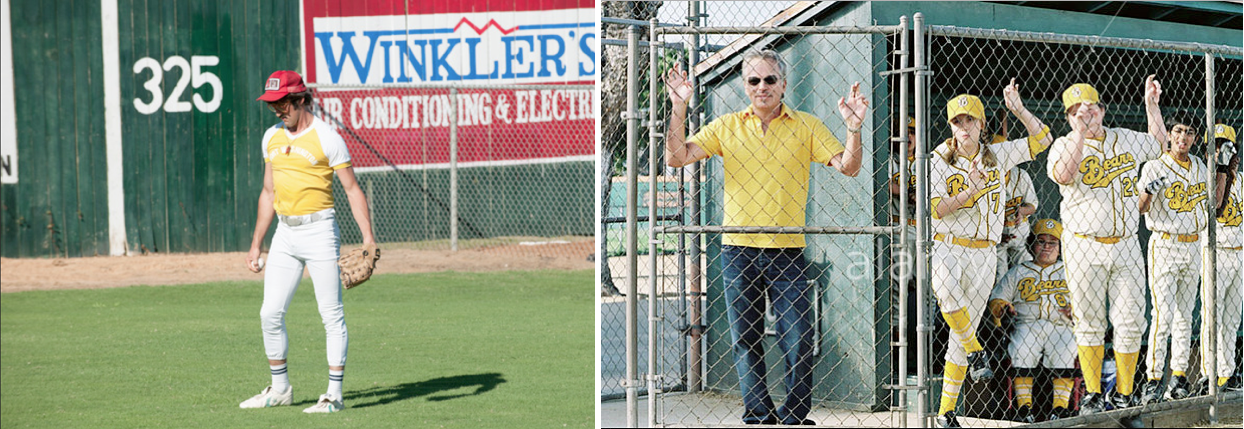

Everybody wants some (sortie prévue en 2016) / Bad News Bear (2005).

Do college baseball players get paid ?

R. L.: No. They get free college though. But it’s like having a job : you spend all your day at practice. It’s a challenge to keep up with your grades. They call you a student athlete, but the school is making a lot of money out of it, particularly football and basket ball. So there’s a controversy that the players should be paid, but they’re not. They get books and tuition and a place to live, but they don’t get any money. It’s against the law to give them cash – it’s corruption.

Did you have a model, someone being both a novelist and a baseball player that inspired you ?

R. L.: No, I wanted to be the first. But in the end I thought the only way to express myself was writing. I didn’t think about writing movies or making movies, so that took a while.

How far did you go into baseball ?

R. L.: Two years of college. But like any pro sports, it’s very difficult. I don’t think I would have made it to the major leagues. I had friends who did, but they were better than I was. We all thought we would, but…

I’m sure you know the show Eastbound and Down. Do you like it ?

R. L.: I saw probably six or seven episodes. It’s very funny. He captures a type : former athletes who get numb when their carrer stops, like they don’t have anything else.

AUSTIN / CINECLUB

Is Austin now very different from what it was when you moved there ?

R. L.: Bigger, but better. There is more financing for culture, a bigger audience. The Film society has always been successful. We used to show experimental films from the 60s, but not only – avant-garde shorts and things. Nobody was doing that. And we did well. The very first program was sold out. The first retrospective we did was Fassbinder – we showed ten films of his – because I wanted to see directors’ retrospective. A hundred people would come to the screening.

When you do a screening, is there always a presentation or a discussion ?

R. L. : Usually, myself or someone else will say a few words to introduce the film. People stay after and talk. We had a Tarkovsky retrospective when he passed away. It was in 1986 or 1987. We screened seven films and we invited Russian scholars. I don’t really like academia that way, but it was kind of fun. I prefer more informal discussions, rather than a lecture about what it is all supposed to mean.

When you moved to Austin, were you the one that started everything there, or… ?

R. L. : The film school has always been there. But yes, I started the Film Society, because the school was showing less and less films. When I first moved there, they had different places on the campus that were showing five films a day. It was great. This is over though. The Film Society model nationwide was sort of dying, in 85-86. Home-video was killing the Film Society. That’s right when we started. Everyone else was dying. In the end, we did well. Austin had a very literate film population; they just didn’t have the right outlet. So we got the publicity, interesting programming, showing retrospectives. Austin is a very music, literary town, but it’s also a film town. It always had been, we just needed to bring that out.

Do you work with South by Southwest ?

R. L. : I know the staff and we have friendly relationships but that’s it. We do not meet on an official or regular basis.

I was there last year when you went on stage to present Bernie. It looked like you were the city’s child prodigy.

R. L. : I like to define myself as the mayor of a crazy town. If you do anything long enough, you become established. I don’t really like Los Angeles. I visit there – my sister lives there. But the film industry’s expansion is suffocating. It is not that bad in Austin. A lot of filmmakers still live there, Terrence Malick, me, Robert Rodriguez, Mike Judge, Jeff Nichols, David Gordon Green, Andrew Bujalsky – a lot of younger filmmakers, in their thirties, who haven’t all made a big name for themselves, but they’re very good – a lot of great documentary filmmakers. The Film Society sponsors their films. We get grants and money donated and give it to the film. You know, you help any way you can. But you can only do so much…

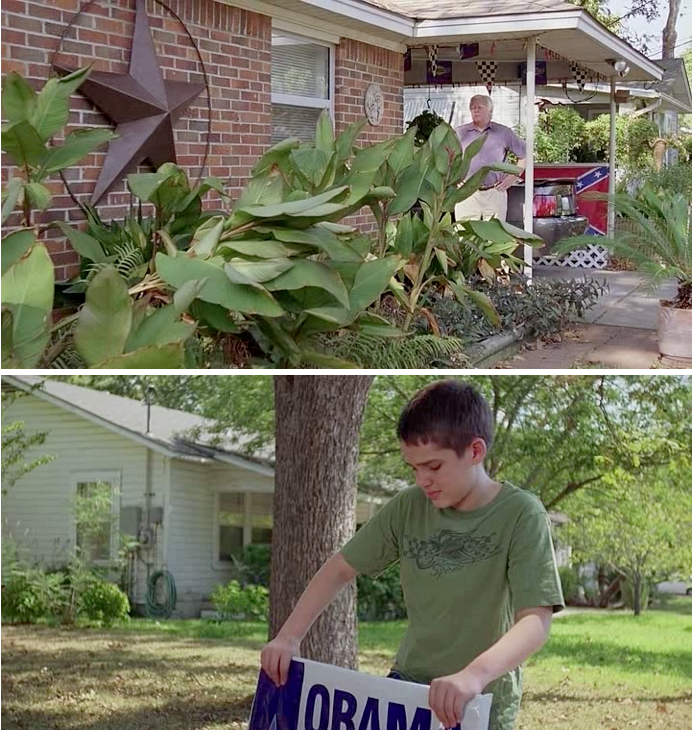

Boyhood (2014).

I’ve been told Austin is very different from the rest of Texas.

R. L. : Yes, it is. I don’t know. Austin hasn’t changed but the rest of Texas has. It became very Republican. It was a blue state up until the late 1970s. But it was Southern. Some of them actually were Republicans. They went from Democrats to Republicans. The politics have always shifted around. It’s currently pretty right-wing, except for Austin, but also other parts : Houston and Dallas voted for Obama. Texas has four of the largest fifteen cities in the whole United States : Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, Austin – these blue dots in a pretty big red state, but they’re pretty big concentration of population, with the Latinos, because we got a lot of immigrants. And the Latinos all vote Democrat. So Austin is going to skip by 2020 – it will be a democratic state again. I don’t know what will happen to all the rednecks, all the conservative people. We have a governor that has been there forever, kind of corrupt.

So you mean Terrence Malick does exist ?

R. L. : Yes, we go to dinner and stuff. He lived in France for a while. His new film, To The Wonder, is about that, with the French wife…

Did you see it ?

R. L. : Yes. That’s the one no one loves that much. Not my favorite either.

I especially don’t like the Parisian part of it. It’s not Paris. And the beginning at the Mont St Michel – it’s… But he has a new one that is almost completed. Have you seen it ?

R. L. : No. He just doesn’t do publicity – he’s of that generation that doesn’t do publicity. But he’s not really a reckless – he comes to our movies. I had dinner with him and his wife a month ago. I see him at events. But only once at a Film Society event did he get up on stage and talk. Which was a big deal.

Was it for a movie of his ?

R. L. : No, we have this fundraiser every year – it’s called The Texas Film Hall of Fame – where we honor movies and people from Texas. It’s the beginning of South by Southwest. 800 people come and we raise a lot of money. It’s like a celebration. And we were paying a tribute to Terrence Malick. I told him we were gonna do it, but he said : « Oh, yeah, but I can’t get up on stage. » And then I think his wife talked him into it. So he got up and spoke. He did it, but he was a little nervous. He didn’t like it. I don’t blame him. I don’t like to speak in public either, but you do it.

What kind of budget did you have when you launched the Film Society ?

R. L. : I only had my credit card. It was like a low-budget film: just one program at a time. We started showing one thing a month – we would do a program once a month. Within a few years, we had our own little theater. I renovated a storage area above a coffe shop. We had a 16mm projection booth. We would show five films in a week-end, which was too much – people didn’t want it.

You also invited Quentin Tarantino.

R. L.: Yes. Quentin and I have been friends for like 20 years. He would come to Austin and show movies. He has a print collection and he will come and maybe show 30 movies in a week. Stay up all night and watch horror films and come out at dawn. He’s fun, he’s like a good film freak friend.

He did that at your Film Society? And everyone can come ?

R. L. : Yes. And anyone can come. It’s like being in your living-room and watching a movie. We started doing that in the 90s and we had a lot of fun with film events.

Are you as passionate a film buff as Tarantino is ?

R. L. : Yes, different kind of movies though. I think we both have an appreciation. When he comes, he mostly picks genre films. One of the last time he came – during a festival about ten years ago – all he showed was revenge movies. He was gearing up his decade of revenge. He did another one about five years ago. He likes it less now, because people have smartphones and they’re filming. He did not really appreciate that. I enjoy revenge movies ; it reminds me of movies I liked when I was 13. But the films I show are much more what you would consider high-brow, like a Robert Bresson retrospective, or Pasolini, or Fassbinder. We show a lot of international cinema. It’s not so much young – although we do a lot of it too. We show everything.

FIRST FILM : SLACKER

You shot your first film in 1988.

R. L. : Yes, I had been shooting in Super 8. I’d already made a couple of shorts. We took the summer off when I shot Slacker and I was working with a lot of the same people who had worked with me at the Film Society. My roommate was a professional assistant-cameraman – he had a focus-puller for commercials. I got them all to work on Slacker. Slacker is not actually my first picture. My first picture is called It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books. It has a very long title – it’s a joke, a Russian proverb I saw on a shirt. You can see it on the Criterion DVD edition of Slacker as an extra. It’s the opposite of Slacker. There is no dialogue and it is just visual. I did it alone for like 300 dollars. It has its fans – some people like it a lot. But it’s a visual experience. I shot it in Super 8. I never even tried to get it distributed. I showed it on an access channel. I did it privatly, completely alone. No one knew I was doing it. I did everything in it. I was a guy running the Film Society, booking films and working on a film too – I was kind of the film guy. So what was very important was that I finish the film. Because a lot of people want to make films, but I proved that I could be the guy that want to make but also finish them. I was driven enough to do that. So when I was going to make a bigger film – which was still a very small film, but I needed a lot more people involved – at least I had completed a feature. Slacker was 23 000 dollars, which is nothing, but a lot when you don’t have 23 000 dollars on your bank account. And that one got distributed. That one was the surprise. That’s the film that really changed everything: it changed my life and Austin’s life too, because it was the first film from some place like Texas that would be taken seriously as an art independent film – that never hapenned though – and that would not be about cowboys, that wasn’t « Southern ».

Slacker was 23000 dollars, which is nothing, but a lot when you don’t have 23000 dollars on your bank account.

How did it get noticed ? Did the movie go to Sundance ?

R. L. : We got rejected from Sundance at first round. Michael Barker at Orion Classics saw it on videotape. John Pearson, who was a producer’s representant, sent it to him. Oh, I know, the first place it got noticed was at the Seattle Film Festival, in the summer of 90. It was a big deal. We had shown it in Dallas some time before and it got a good audience response, but critical response was like : « It should have been a short ». They just dismissed it. That’s Texas, you know – we hate ourselves. So I remember being at this festival in Seattle. It was just ahead of the grunge music scene. It was like a big screening for us, and the people who programmed the festival really loved the movie. I remember going and they had promoted it so much, like « This is the best film » and I remember standing outside the theater, watching the people in the line. But in Seattle, they were like « This is the best indie film of the year ; don’t miss it ». And I saw the line and they all look like people who were in the film, dressed a certain way. And I was like « That’s the audience! », you know: young, disaffected. Just a cultural moment. By the time it came out in 91, the Douglas Coupland book Generation X and Nirvana’s « Nevermind » had come out, and there were all these magazines articles like « Nirvana is the best band ; Slacker is the film ; Gen. X is the book ». It only takes three pieces of work to make a cultural movement.

Were you conscious of that at the time ?

R. L. : Yes, it was obvious that it was like: young people, experimental narrative, everything about it. It was a moment – a cultural moment. But I knew I would never live up to that. My ideas for films didn’t have much to do with the generation. But the next one kind of did. Dazed and Confused was like it fits that. I think when I did Before Sunrise, everyone realized I was somewhere else. Even though they tried to make it a Gen X romance, it really wasn’t. It didn’t have anything to do with 1994 or 1995. So I sort of drifted away with generational spokesperson. Film and politics, as Lindsay Anderson, one of my mentor, said, are kind of ships passing in the night – you cross for a second and then you go your separate ways. Sometimes your film is culturally relevant, sometimes it isn’t. I kind of like the one that aren’t. I like these films that are just a moment in time. I remember The Newton Boys – that’s when I got really kicked out of the club, because that took place in 1918 to 1922. It starts off western and ends up a gangster movie – the two great genres. They do their first robbery on horseback and the last, they’re like gangsters in Chicago. It’s all a true story; it all really happened, so I was kind of obsessed with that.

You said you got « kicked out », what do you mean ?

R. L. : I just said that metaphorically, I think. That’s when they knew they coulndn’t trust me at all to be a good boy. I was sort of kicked out of Hollywood, I think. But it was easy to kick me out of Hollywood because I was just a visitor there anyway. They never tell you you’re kicked out, you just realized they’re never funding anything you want to do.

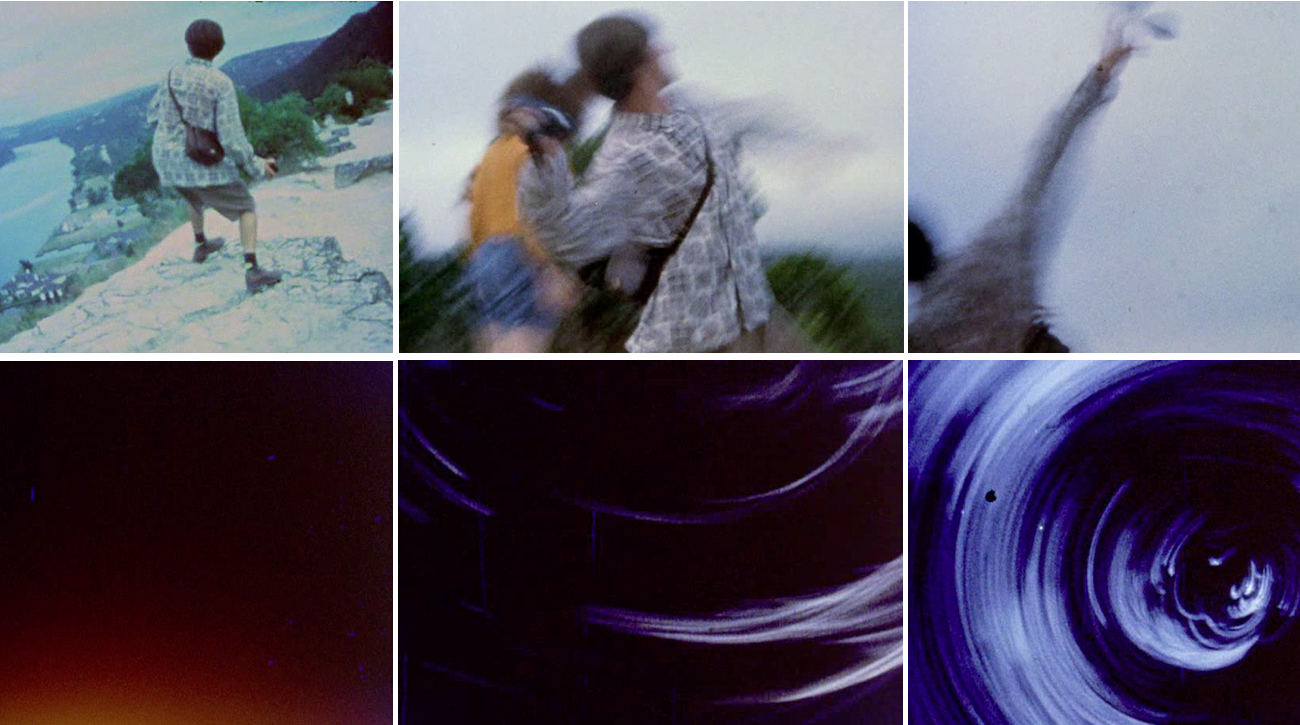

Slacker (1988).

The Newton Boys, you shot it in Los Angeles or in Texas ?

R. L. : In Texas. It’s a very Texas movie.

You never actually did a movie in Los Angeles.

R. L.: I did actually, years later. I did two studio films : The School of Rock in 2003 and Bad News Bears en 2005. Both were for Paramount and were a good experience. Because we shot it during winter and we needed it to be summer, so we shot in LA for the weather. And Billy Bob Thorton was living there and couldn’t leave. So I made the most of it; I wasn’t happy to be there but it was good to have that experience once. That was easy – I liked working there at that time. Sherry Lansing run the studio, she liked me a lot and let me do whatever I wanted. She had a lot of faith in me. It was just like shooting an independent film.

The School of Rock is sort of a classic now.

R. L.: Yes, it became that. I shot that in New York, even though it’s not set in Manhattan. That was a good experience too. I think we’re going to have a ten years reunion in September for School of Rock, with all the kids that have grown up.

You’ve been your own producer most of the time.

R. L.: Yes. You work with other producers, but I don’t even know what that means, « to produce »… You just get the money somewhere and… It’s always difficult, but in the end it happens.