Cet article fait partie d’un cycle

Last August, the Locarno International Film Festival dedicated a retrospective to the work of Sam Peckinpah. In September, the Cinémathèque française took this tribute over. At the Café des Images, we seized the opportunity to host a special Peckinpah evening on Thursday the 1st of October. The screenings of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973) and Cross of Iron (1977) will be introduced by our guest Fernando Ganzo, a film critic and head of publishing team for Sam Peckinpah, a collection of essays recently available in bookshops both in French and English thanks to Capricci. Here is an excerpt from “Spurs, the styles of Sam Peckinpah”, by Emmanuel Burdeau, covering for years 1969 to 1973 of the American director’s carreer. This opens a special Peckinpah series made up of additional texts coming soon online on the Café en Revue.

A sequence of about eight minutes opens The Getaway. Its setting is a prison in the state of Ohio where Carter “Doc” McCoy is serving ten years for armed robbery. A series of images explores the interior, and sometimes the exterior. They depict “Doc”’s cell, the hearing where he is refused early release, the comings and goings in the corridors, the work of the prisoners within the walls, and their activities in the surrounding fields. They also offer glimpses, whether memories or premonitions, of “Doc” embracing his wife.

Each of these visual snippets proceeds at its own pace. The whole piece plays out at a variety of rhythms from immobility to furious speed. Immobility: a deer sitting in the stable yard looking toward the camera is changed into a logo by a freeze-frame with the text “First Artists”. Furious speed: the machine looms on which “Doc” and the others busy themselves make a racket which continues in the background of scenes which have nothing to do with the work. This deafening noise provides an industrial atmosphere for events only some of which are under the reigning discipline. Inmates enter their cells in synchrony and are lead out to the fields in order, with the guards keeping count as each one passes through a gateway. On the other hand, taking a shower, playing chess, weightlifting in the exercise yard, the attentiveness of the doe: all answer to exterior causes, or to no cause at all. The cadence seems at times military, but there is also a music that comes from the rhythm of the events. “Doc” and a fellow prisoner exchange high fives between two grilles and, conjured as by a snap of the fingers, this salutation brings a new title- over-picture, in white letters, “The Getaway”. The film begins.

The eight minutes that introduce this adaptation of the novel by Jim Thompson are among the most accomplished sequences in the work of Sam Peckinpah. Their crescendo culminates in a scene where “Doc” in his cell destroys the bridge which he has built out of matches, one imagines to kill time. The offstage din of the workshop increases while the succession of images becomes even faster. Flashes of Carol, his wife, mingle with clips of men showering, and views of the warders on horseback with those of the prison workshop machinery in action.

This opening plays on two competing meanings of the word “enchain”. “Enchainment” was a major preoccupation of Sam Peckinpah in these middle years from The Wild Bunch to Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid. Its first sense: the cinema’s capacity to link images and sounds and draw out from them new relationships. And the second: what society does to a man when it locks him away for the length of his sentence. A positive artistic meaning: a negative take on power. Art that liberates by linking things differently contends with the power which oppresses. The first enchainment prepares for, and even accomplishes, emancipation; the second, literally, puts into chains.

Between these two senses, Peckinpah and his film editor Robert J. Wolfe provide a series of linkages and dynamic reverses. These linkages and reverses could have for their controlling force the handle with which “Doc” controls his machine loom. In the midst of a rich and complex montage, this lever provides a direct – or the least indirect – metaphor for the cutting table where one can imagine Peckinpah and Wolfe at work. When “Doc” – that is to say Wolfe, that is to say Peckinpah – pushes the lever, imprisonment reverses, releasing a burst of energy: the rhythm accelerates, the regime is interrupted by a bucolic moment or a sensual vignette. When “Doc” – that is to say Wolfe, that is to say Peckinpah – pulls it back, the visions of liberation collapse under the weight of the law: order returns, a re-establishment of regulation. The reverse is also conceivable: push to lock, pull to release… the metaphor is flexible.

A superb opening. Risky too. A high-wire act. But what’s to say that these minutes don’t just end up as industrial art, the machinery of the prison taking precedence over the machinery of the cinema? Nothing more than a new imprisonment? For sure, there is no complete protection against such a risk. Always, the liberty conferred by the edit is at risk of suffering the subjugation of Power. But in neither of the senses of the word enchainment is the undertaking worthwhile unless in a situation of precarity where humanity and the cinema are both in a state of need. So what to do? It is necessary not only to create the conditions of liberty, but also to liberate from the (same) conditions. Not to pick sides on the meaning of the word, but to release the construct and its interpretation. To enchain and to “disenchain” is not enough: it is as important to unchain, and never mind if everything collapses like a card-house.

To enchain and to “disenchain” is not enough: it is as important to unchain, and never mind if everything collapses like a card-house.

Such “disenchainments” appear again and again. In his white prison garb, “Doc” has a severely neutral appearance, with all the impassiveness that Steve McQueen carries off so well, at once fearless and self-contained – not wanting to be misunderstood again. When he expresses his frustration with being confined, it’s with a cold, wordless rage: here he crushes the matchstick bridge, there he knocks over the pieces on the chessboard during a match with another prisoner. These miniatures epitomise the sequence: Peckinpah constructs a mosaic with one hand and destroys it with the other; he carefully lays out the pieces which he will soon send flying; he builds bridges between gestures and images only to blow them up a second later. (There are castles and bridges of less symbolic import destroyed in other works, for example in The Wild Bunch; one can always find in them the simulacra of montages, of enchainment, of “disenchainment” and of unchainment.)

The alternation of scenes is so fast and varied that the impression of a finely- tuned mechanism competes on equal terms with that of a mishmash. Peckinpah and Wolfe offer us the spectacle of a closed world, where the clangour of the gates, the guards high in their watchtowers, the constriction of the cells, the perfectly regimented column of prisoners all work together – and all keep in time. A logical circuit where everything is related to everything else, inescapably. Peckinpah and Wolfe reveal at the same time the panorama of a world that has lost its head. It’s all a dance: links are energised which lack any proper causal relationship. A doe rhymes with a watchtower. There are so many entrances and exits from the cells that one loses count. An extreme close-up of Carol stroking “Doc”’s forehead arrives like an interruption: here is not disorder subdued by order, but order and peace and love coming to the relief of the mental chaos suffered by the detainee. Strange connections which flip the inside and the outside, the before and the after, the loss of liberty and its reclamation. Connections without any logic other than that of wanting to destroy the logic that reigns in this place and to increase, in this pressure- cooker, “Doc”’s fury.

As often is the case in Peckinpah’s work, here the machine and the animal are at two extremes. The machine loom stands for activity and regulation. It represents the movement and the authority which proclaim themselves universal. As for the animal, it is associated from the start with the freeze- frame; it incarnates stillness, not only another dominion, but a refusal to accept the logic, or the absence of logic, of the relationship. Before further discussion of the machine we must now focus on animals, because it is they who, in many respects, come first.

The ruin of the machines and the animal (Junior Bonner / The Ballad of Cable Hogue).

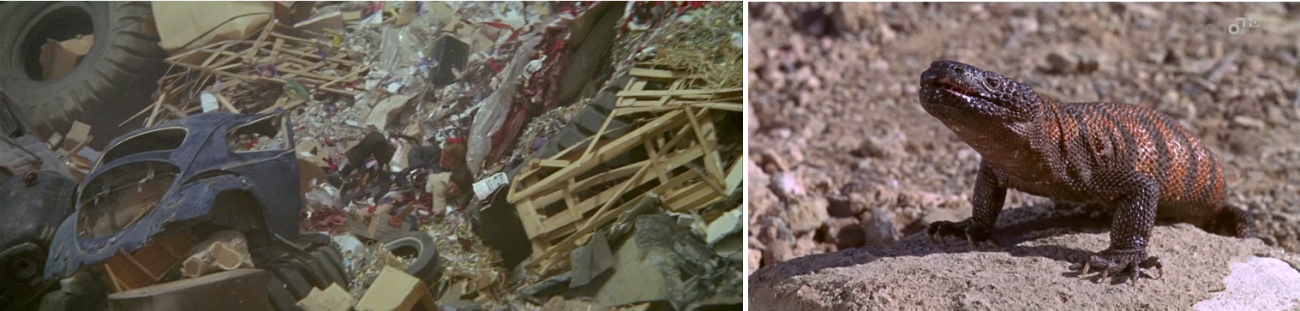

When one underlines their importance in the work of Peckinpah, it is usual to point out the extent to which animal cruelty – their cruelty to each other and man’s cruelty to them – echoes the violence that these films have become associated with. It is true that the scorpions being offered to an ant colony by the children prefigures the blood-bath at San Rafael at the beginning of The Wild Bunch. The link between one massacre and the other is indisputable: the scene of the children setting the insects alight dissolves into the victims that Pike Thornton’s men and the railway company are going to strip like scavengers. It is true that at the beginning of The Ballad of Cable Hogue, Hogue stumbles on an iguana in the desert, which, famished, he prepares to make a meal of before being stopped by the gunfire of his two associates, who reduce the lizard to mincemeat. And it is true that at the beginning of Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, the hens that the Kid and his buddies shoot at to relieve their boredom explode in a horrible vision clearly anticipating deaths to come.

The enumeration of so many animals however is insufficient, nor is it enough to point out their close link with the motif of violence. One has to start with what is most basic and most crucial: the animal comes before anything else, before any other creature; they open the films, often if not always. The beginnings of The Getaway and The Wild Bunch, The Ballad of Cable Hogue and Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid. And the beginning of Straw Dogs: in a cemetery in Cornwall, children form a circle around a dog. And finally the beginning of Junior Bonner, allowing us to admire the bulls and horses of the rodeo where the title character works.

The animal is readily associated with childhood; it appears before the setting- in-motion of the grand apparatus of linkages of which the first minutes of The Getaway are a prime example. The animal comes before enchainment – before all enchainments, the good and the bad. The doe is followed by deer and horses, but its transformation in a freeze-frame gives it a special significance. It may be that the animal is essentially that, for Peckinpah: a logo, a mascot. A pure sign that means nothing beyond what it is. If not quite a signature then the expression of the idea that it might be possible to sign off with a snout or a pair of wings. Denied language and communication, the animal is in a position to protest, silently, against tyrannies and expedients, impatience and misunderstandings. The animal is alone; its image is at liberty, it belongs only to itself, (a) still not requiring manipulation. Its apparition carries something – momentarily, forever – that the rest of the film can only contradict.

Two timings, at once irreconcilable and profoundly intertwined, dominate Peckinpah’s work. Both are present in the opening minutes of The Getaway: the tempo or era before the violence and the tempo or era when violence reigns. His œuvre is the story of forces which work together to overturn one time for another; it is also, one tends to forget, the story of the forces which fight to the bitter end against the direction of the swing. Before that – before the invention of the cinema – an equilibrium could be found, thanks to the animal, between the free and the enmeshed, between the sovereignty of those who stay outside of language and those who are enlisted in games of crusader cruelty, in which nothing limits recourse to, or the fatal necessity of, enchainment and its consequences. The animal doesn’t represent anything and yet it is the object of all associations and every metaphor. The animal is outgunned in every way, something which always fascinates Peckinpah. It is primary, in such a way that one can consider the propensity of Peckinpah’s cinema to violent relationships, and to violence itself, to be secondary.

Major and minor / The Montages

The title sequence of The Getaway isn’t the only one of its kind in Peckinpah’s filmography. The Wild Bunch and Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid also each open with one. In both of them, the initial scenes feature transitions: in one, from movement to immobility, and in the other, from colour to a solarised black and white. In The Wild Bunch, the members of the gang making their approach along the main street of San Rafael to attack the railway company office, disguised as Texas Rangers, are outlined in freeze-frames for the opening credits. In Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, the elderly Pat Garrett is likewise fixed in a moment of time, falling from his horse under a hail of bullets in 1909, a scene transported nearly thirty years from the drama of the original event in 1881.

The Wild Bunch and Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid also feature similar chase scenes. In the first, the gang led by Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan) goes after that of Pike Bishop (William Holden). In the second, the “Kid” (Kris Kristofferson) is pursued by the Sheriff (James Coburn). These two pursuits have in common a combat between old friends and brothers-in-arms for whom the passage of time, different careers, treason and compromise have not quite broken the ties between them. Each of these pursuits seems to go on endlessly, as though the hunters were actually in no hurry to catch their prey. As though the goal were not so much the confrontation itself as the delay in arriving at it. For Peckinpah it is always the moment of contact that is most sensitive: the moment both the most desirable and the most dangerous. Just as the opening moments of The Getaway confront imprisonment with freedom, The Wild Bunch and Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid both seem to contain – by way of changes of pace and cross-cuts, missed opportunities and chance meetings, momentary set-backs and sudden leaps – a hidden desire for an interstitial rupture to create a void broad enough that the characters on both sides may fall in and never again emerge. What other way to escape the carnage? If Deke Thornton and Pike Bishop, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid were all to disappear into the limbo of a splice between two scenes, we could conclude they had reached the goal that they had always sought, not separately or in competition, but in a blessed unity.

The aim of this text is to reflect on how the sequences and edits of Peckinpah’s cinema yield up their truth. Where is that truth to be found? In what relationship between the story as reported and that unreported, between transitions and breaks in continuity? My hypothesis is as follows. That if this cinema has a place, then that place is in the strange interval between the singularity of images and the product of their assembly; between lonely (story-) lines advancing in parallel and those that meet; between separation from old friends and inevitably meeting up with them again; between the free use of film-editing techniques – even unto the bizarre, the nonsensical, the ecstatic – and the need for the scenes – linked together, or perhaps colliding – to nevertheless make sense.

Particularly in these middle years when his compositional skill was at its height, it seems that Peckinpah wanted to keep to the creative high ground, a place where a cinema “deconstructed” into fragments – or in tatters – had the possibility of linking up with another kind of cinema, one enamoured of rhyme, music and History. To sum up: on one hand the structure, on the other its negation. One hasn’t got a chance of understanding the representation of violence in Peckinpah’s work without taking into account this constant dichotomy of inspiration. No doubt this also provides an explanation for several of the filmmaker’s problems: chaotic shooting, budget overruns, an increasingly bad reputation, movies massacred by the studios… Thus the intent of Peckinpah’s oeuvre was in effect towards the destruction of the cinema, even if it put his own ability to work seriously at risk. How did these two opposing forces function together, against and beyond their limitations? By what effort, or contrariwise, by what accommodation, does one pass between them? How does the cinema speak to the question of destruction, while itself seemingly torn between discourse and destruction? Those are my questions.

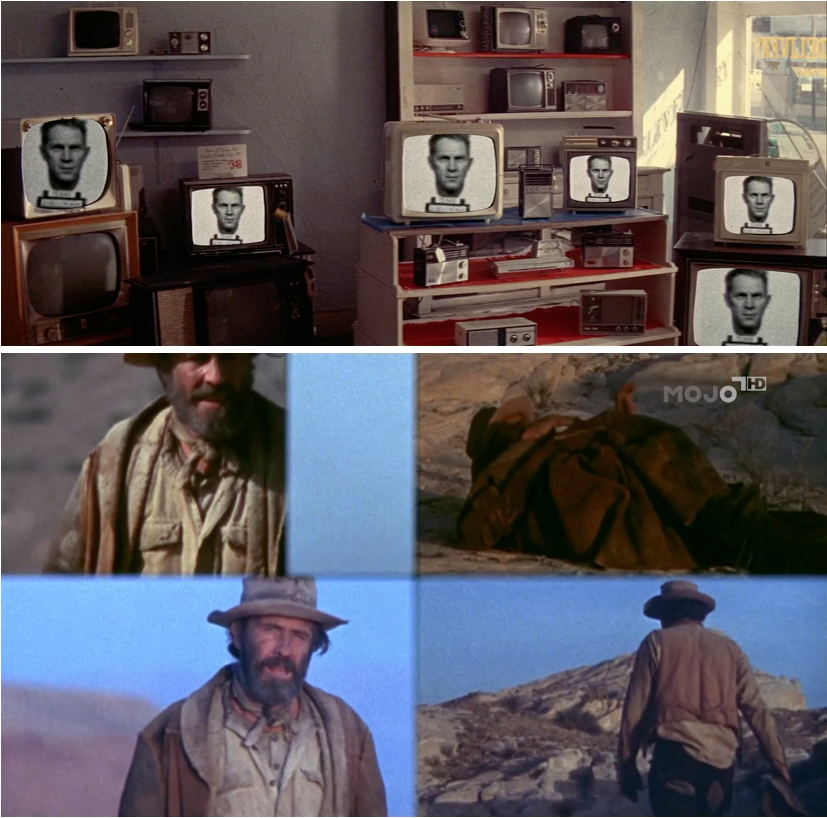

Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid.

The system which has been described at the beginning of The Getaway applies at the start of other films: the self-sufficiency of the animal and the great mechanism of montage interlinking everything, the stillness of the beast and the work already in progress, if not already done… I have mentioned the connection made in The Wild Bunch between the scorpions and the ants on one hand and the killing at San Rafael on the other; it is also a connection between childhood and adulthood, which wouldn’t be so cruel if there weren’t in Thornton’s gang a particularly unkempt simpleton, the aptly named Clarence “Crazy” Lee. Another connection occurs later which briefly brings together two old friends against all odds. One evening out on the trail, Pike Bishop recalls wistfully his escapades with Deke Thornton, their last moments together, the recklessness that almost cost the life of his partner. Several brief flashbacks follow. On the other side, once back in the present, the viewer finds not Pike but Deke, in a similar position, also thoughtful and as though emerging from the same reverie. A link still therefore exists between the two men, between the past and the present, but only in the imagination, a strictly mental connection with no reality other than a hallucination shared between them by the cutting of the film.

At the beginning of Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, as mentioned, the Kid and his buddies kill time by shooting at hens. Then there’s more: an unexpected jump and the shots are being fired at Pat Garrett riding his horse thirty years later. A recreational moment morphs into murder, or even suicide, Pat soon joining the gunmen. 1881 has infected 1909. Everything is mixed up. One seems to recognise Kris Kristofferson beside James Coburn, looking older and more lined than he’ll look seven years later in the epilogue to Heaven’s Gate by Michael Cimino. The Kid’s been dead for ages, but his ghost endures to ride alongside Pat Garrett. The future is in the present: that’s the significance of these bullets, fired at the hens and hitting the old man. And the past is in the present: that’s the meaning of the ghostly rider, this glimpse of a spectre seen again. Of course one can talk of obsession. The word has its place, but it should be balanced against another, less poetic: confusion. There is confusion in Peckinpah. It is pointless to deny it: this is the price of the power of his cinema.

It’s done as though in error, from one shot and one edit, from one scene and one date – 1881/1909 – to the other. Like a wrong turning that’s both joyful and dire and which ends the drama before it begins. This short-circuit is no less typical of Peckinpah than the mechanical complexity of The Getaway. I have introduced the idea that mathematical intelligence is one thing, but it’s not everything; only by adding a measure of disorder to the mix can a filmmaker find the freedom they need. Film editing must be elevated to the status of a major art form, but it is just as important that it be practised as a minor art, or even practised as an insult to its claim to the status of an art. To show the truth in images, there must be some where stray bullets fly: they hit the target too, and sometimes more surely.

The study of Peckinpah’s work can’t be captured in a single motif. Its manifestations are protean and asymmetrical. Some of his films are in a major key, a cut that is structured and clear: the opening of The Getaway, most of Straw Dogs… In others, The Wild Bunch and Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, there’s an alternation between clarity and confusion, major and minor keys. Finally there are the films in which a minor key predominates: The Ballad of Cable Hogue and Junior Bonner, to name only those in the period under discussion. The importance of The Ballad of Cable Hogue and Junior Bonner is certainly no match for that reached in the history of modern cinema by The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs and Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid. Between the animal and the montage, the movement that flows in these two films doesn’t achieve the admirable rigour of the opening of The Getaway. But that is precisely their interest: Cable Hogue and Junior Bonner bring into the open a happy nonchalance that is always potentially present in the work of Peckinpah, but is generally hard to spot.

Splitting the screen (The Getaway / The Ballad of Cable Hogue)

These two films do not begin with clever craftsmanship. The split-screens are so whimsical that they border on parody. The screen is divided into two, three or four parts – of varying sizes – opening and closing like shutters, in one a close-up showing Cable Hogue wandering through the desert, as well as his appeals, imploring or angry, directed at God. The opening of Junior Bonner, the first of two films made in 1972 with Steve McQueen, looks for its part like a cheap version of that of The Getaway. The same cobbled-together effects as before – almost exactly – mixing sepia and colour, images of the rodeo and those of the hero returning disappointed to his caravan. Junior sticks his hat on one last time, the timer set in motion, the eye of the bull, a hand releases the gate, the sound of the bells on the beast’s neck, and, in alternation, JR returning exhausted to the stables, still the sound of the bells and of his spurs, and he sets off again…

A series of comic situations confront Cable Hogue (Jason Robards) with the plunging neckline and bosom of Hildy, the prostitute played by Stella Stevens. As if it were itself also moved, the face engraved on the banknote he has in his hand gives a smile which is enough to convince Hogue to treat himself to a little pleasure. And in the desert where he has miraculously found a spring, fast motion accompanied by music evocative of that of a Benny Hill Show provides further evidence that Peckinpah can use the manipulation of images to deliver cartoon-like gags very different from the constructivism he practices elsewhere.

As for Junior Bonner, there are of course freeze-frames, but also fast motion and a huge saloon brawl on the margins of which Bonner and Charmane share a first kiss. The film evokes a pastiche of a Western transposed into the America of the 1960s. Other jingles, also worthy of Benny Hill; shots that zoom in on a competitor’s blood-stained boot or adjustment of a glove; the buzzer that launches them into the arena: all raise – or lower – the tone of Cable Hogue’s lesson. The weirdness of Peckinpah lies not in the peals of loud laughter (those of The Wild Bunch are unforgettable) of its heroes, whose faces are ravaged by the sun and by adversity; it is also in the rhythm, the sound and the content of the scenes themselves, where there is no reluctance to grimace and play the fool.

From refined to rustic, his staging and montage cover the whole spectrum. From one extreme to the other there is in his work both the subtle and the antithesis of subtlety. Peckinpah shows us more than one face. Sometimes he composes his films in the guise of a baton-wielding orchestral conductor. On other occasions he appears, less rehearsed, as a straightforward singer, brother of those he likes to film: Bob Dylan in Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, Kris Kristofferson in that film, then in Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia and in The Convoy. Here one could say that his films are improvised like a fireside ballad, like that of Cable Hogue, and again, that of the “Rubber Duck” (Kristofferson) in The Convoy, which is composed by his admirers along the course of his journey.

Peckinpah at times evokes an American offspring of the formalists of the 1920s, a kind of Eisenstein soaked in tequila.

Peckinpah at times evokes an American offspring of the formalists of the 1920s, a kind of Eisenstein soaked in tequila. He is undoubtedly one of the most brilliant filmmakers/film editors of history. But sometimes on the contrary his films seem so laid-back that one feels inclined to see him as a director who is all “zoom-zoom” on the cutting table and is thinking of other things while he directs. One has to keep in mind that Peckinpah began his career in television and that’s where he ended, in a way, with The Osterman Weekend, which deals with surveillance and the new ubiquity of images.

And so one has to weigh one’s words carefully when talking about Sam Peckinpah as a great filmmaker. One must pay attention to what that means: the term is appropriate for the first few minutes of The Getaway and for the bravura segments of The Wild Bunch and Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid. But is it appropriate for the amusing ventures The Ballad of Cable Hogue and Junior Bonner? Peckinpah needed these zooms and artifices, these comic effects and straight-out comedy, to give him access to further possibilities for filmic creation, alongside the more sensational ones which he knew how to formulate so well. Should one judge him less great to have agreed from time to time to descend a few steps on the scale of his pretensions? One would have to say yes if one considers greatness the ability to choose one’s standards and then stick to them. And one would say no if one chooses to ignore the second-rate Peckinpah and retain only the other: the first, the flamboyant, the Soviet.

One can also say no without having to make that choice. Some filmmakers are great in their differentiation, others by that which they work to reveal. Peckinpah’s greatness lies in his openness and in his dissolution. There is no exclusivity in his work. His art tolerates, if not pettiness, that which others would quickly reject as being too easy. His greatness is inseparable, as we shall see with Straw Dogs, from a hazardousness directed at everything including itself, to which he applies method as much as, sometimes, blind fury.

Translated from French by Colette de Castro.