Leaving the movie theater

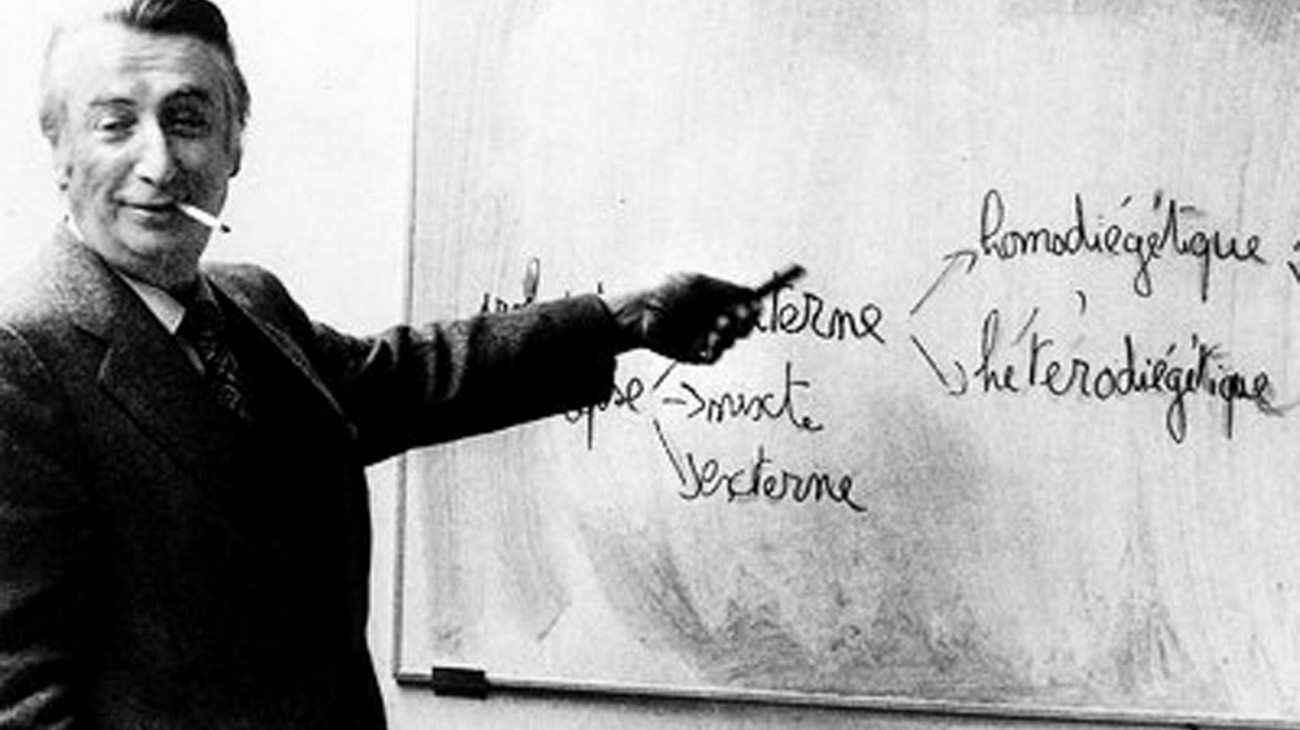

– par Roland Barthes et Patrick Wang

Mulholland Drive, David Lynch, 2001.

Voir les 1 photos

Cet article fait partie d’un cycle

We are glad to publish Roland Barthes’ “Leaving the movie theater”, that you may want to read in its original French context here. We seize the occasion of Barthes’ hundredth anniversary, celebrated this year, and the release of Patrick Wang’s The Grief of Others. The director and his team thought this release in an unusual way with careful attention and Patrick Wang explains it on the film official website. We reproduce this note here, intermingled with Patrick Wang’s comments on the French philosopher’s words. From this fourty years old text up to this brand new film and mutations theaters are going through nowadays, we heard echos that seemed to justify this link. In the coming weeks, we will discuss Roland Barthes again with the complicity of Jean Narboni.

“It is a confusing time for independent film in movie theaters. Theatrical play is seen as a passing, practical means to some other ends or as a strange vestige of the old way. But to me it is the end game. The Grief of Others is whole and at its best quality in a theater. Its themes are the necessity of common ritual and the dangers of isolation, and so it should not be viewed alone. Quality and community are not fringe issues. They should point the compass.

Quality and community are not fringe issues. They should point the compass.

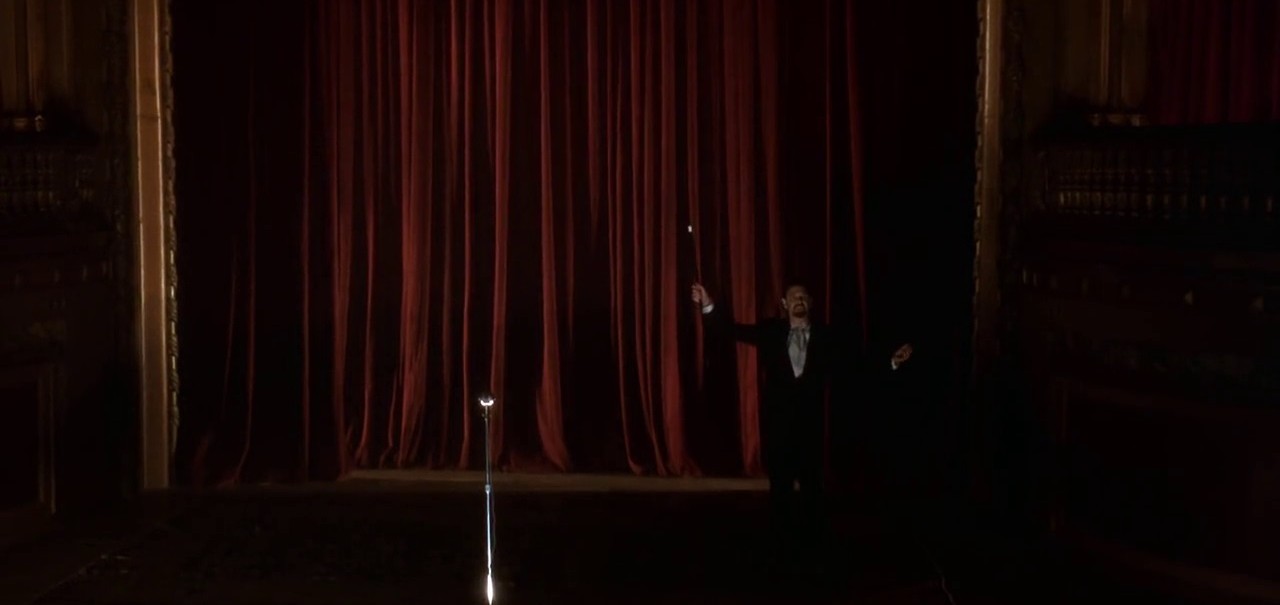

Discovering this text of Roland Barthes, I was struck by how he describes the experience of seeing a film in a theater as a hypnotic state. This is not work or leisure but a therapeutic endeavor. A chance to dig deep into ourselves past the masks of consciousness and daily habit. How few opportunities there are in contemporary living to tend to our deeper selves. Every day brings new inventions to distract us from doing so. Barthes identifies one key to this hypnotic space as the dark. I have to agree. One of the great enemies to immersion in a film is ambient light. As a film works to transport you away from the specifics of your daily living, illuminating the objects of your home seems the most absurd thing to do.

I like how Barthes identifies a third space that is the goal of a movie experience. It is not the literal space where the movie is shown. It is not even the space where the narrative of the film takes place. It is the space we arrive when we see our lives reflected in the mirror of the film. The deeper the hypnosis, the more freely and imaginatively we see this reflection and understand ourselves.

For The Grief of others, we will experiment in search of a modest, sustainable place for an independent film in the movie theater. Rather than play 35 shows a week, we will play just one show a week over many weeks. My hope is that we could run for years this way, like plays do. Maybe we will end up adjusting the interval of time between screenings. But I do not anticipate a digital or home video release. We will stick to theaters. Say we end up screening the movie once a month, and say we do that for the next ten years. Sometime in the next ten years, you may come through New York. Join us for a screening. It’ll be the only way to see the movie, and it’ll be grand.”

Patrick Wang

Leaving the movie theater

“There is something to confess: your speaker likes to leave a movie theater. Back out on the more or less empty, more or less brightly lit sidewalk (it is invariably at night, and during the week that he goes), and heading uncertainly for some café or others, he walks in silence (he doesn’t like discussing the film he’s just seen), a little dazed, wrapped up in himself, feeling the cold – he’s sleepy, that’s what he’s thinking; his body has become something sopitive, soft, limp, and he feels a little disjointed, even (for a moral organization, relief comes only from this quarter) irresponsible. In other words, obviously, he’s coming out of hypnosis. And hypnosis (an old psychoanalytic device – one that psychoanalysis nowadays seem to treat quite condescendingly) means only one thing to him: the most venerable of powers: healing. And he thinks of music: isn’t there such a thing as hypnotic music? The castrato Farinelli, whose messa di voce was « as incredible for its duration as for its emission », relieved the morbid melancholy of Phillip V of Spain by singing him the same aria every night for fourteen years.

Obviously, he’s coming out of hypnosis.

***

This is often how he leaves a movie theater. How does he go in? Except for the – increasingly frequent – case of a specific cultural quest (a selected, sought-for, desired film, object of a veritable preliminary alert), he goes to movies as a response to idleness, leisure, free time. It’s as if, even before he went into the theater, the classic conditions of hypnosis, were in force: vacancy, want of occupation, lethargy; it’s not in front of the film and because of the film that he dreams off – it’s without knowing it, even before he becomes a spectator. There is a « cinema situation », and this situation is pre-hypnotic. According to a true metronomy, the darkness of the theater is prefigured by the « twilight reverie » (a prerequisite for hypnosis, according to Breuer-Freud) which precedes it and leads him from street to street, from poster to poster, finally burrying himself in a dim, anonymous, indifferent cube where that festival of affects known as a film will be presented.

***

What does « the darkness » of the cinema mean? (Whenever I hear the word « cinema », I can’t help thinking « hall », rather than « film ».) Not only is the dark the very substance of reverie (in the pre-hypnoid meaning of the term): it is also the « color » of a diffused eroticism; by its human condensation, by its absence of worldliness (contrary to the cultural appearance that has to be put in at any « legitimate theater »), by the relaxation of postures (how many members of the cinema audience slide down into their seats as if into a bed, coats or feet thrown over the row in front!), the movie house (ordinary model) is a site of availability (even more than cruising), the inoccupation of bodies, which best defines modern eroticism – not that of advertising or strip-tease, but that of the big city. It is in this urban dark that the body’s freedom is generated; this invisible work of possible affects emerges from a veritable cinematographic cocoon; the movie spectator could easily appropriate the silkworm’s motto: Inclusum labor illustrat: it is because I am enclosed that I work and glow with all my desire.

In this darkness of the cinema (anonymous, populated, numerous, – oh, the boredom, the frustration of so-called private showing!) lies the very fascination of the film (any film). Think of the contrary experience: on television, where films are also shown, no fascination: here darkness is erased, anonimity repressed; space is familiar, articulated (by known objects), tamed: the eroticism-no to put it better, to get across the particular kind of lightness, of unfulfillment we mean: the eroticization of the place is foreclosed: television doomed us to the Family, whose household instrument it has become-what the hearth used to be, flanked by its communal kettle.

On television, no fascination: here darkness is erased, anonimity repressed; space is familiar, articulated (by known objects), tamed.

***

In that opaque cube, one light: the film, the screen? Yes, of course. But also (especially?), visible and unperceived, that dancing cone which pierces the darkness like a laser beam. This beam is minted; according to the rotation of its particles, into changing figures; we turn our face towards the currency of a gleaming vibration whose imperious jet brushes our skull, glances glancing off someone’s hair, someone’s face. As in the old hypnotic experiments, we are fascinated -without seeing it head-on- by this shining site, motionless and dancing.

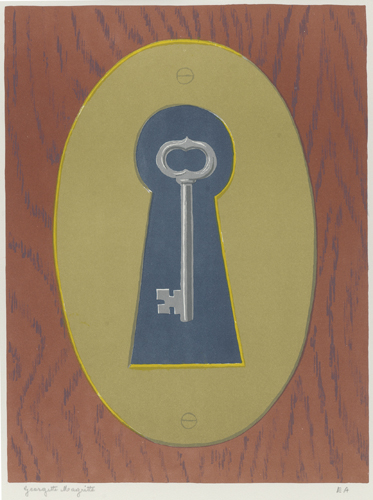

The Smile of The Devil, René Magritte, 1967.

It’s exactly as if a long stem of light had outlined a keyhole, and then we all peered, flabbergasted, through that hole. And nothing in this ecstasy is provided by sound, music, words? Usually -in current productions- the audio protocol can produce no fascinated listening: conceived to reinforce the lifelikeness of the anecdote, sound is merely a supplementary instrument of representation; it is meant to integrate itself unobtrusively into the object shown, it is in no way detached from this object; yet it would take very little in order to separate this sound track: one displaced or magnified sound, the grain of a voice milled in our eardrums, and the fascination begins again; for it never comes except from artifice, or better still: from the artifact-like the dancing beam of the projector-which comes from overhead or to the side, blurring the scene shown by the screen yet without distorting its image (its gestalt, its meaning).

***

For such is the narrow range -at least for me- in which can function the fascination of film, the cinematographic hypnosis: I must be in the story (there must be verisimilitude), but I must also be elsewhere: a slightly disengaged image-repertoire, that is what I must have-like a scrupulous, conscientious, organized, in a word: difficult fetishist, that is what I require of the film and of the situation in which I go looking for it.

***

The film image (including the sound) is what? A lure. I am confined with the image as if I were held in that famous dual relation which establishes the image-repertoire. The image is there, in front of me, for me: coalescent (its signified and its signifier melted together), analogical, total, pregnant; it is a perfect lure: I fling myself upon it like an animal upon the scrap of “lifelike” rag held out to him; and, of course, it sustains in me the misreading attached to Ego and to image-repertoire. In the movie theater, however far away I am sitting, I press my nose against the screen’s mirror, against that “other” image-repertoire with which I narcissistically identified myself (it is said that the spectators who choose to sit as close to the screen as possible are children and movie buffs); the image captivates me, captures me: I am glued to the representation, and it is this glue which established the naturalness (the pseudo-nature) of the filmed scene (a glue prepared with all the ingredients of “technique”); the Real knows only distances, the Symbolic knows only masks; the image alone (the image-repertoire) is close, only the image is “true” (can produce the resonance of truth). Actually, has not the image, statutorily, all the characteristics of the ideological? The historical subject, like the cinema spectator I am imagining, is also glued to ideological discourse: he experiences its coalescence, its analogical security, its naturalness, its “truth”: it is a lure (our lure, for who escapes it?); the Ideological would actually be the image-repertoire of a period of history, the Cinema of a society; like the film which lures its clientele, it even has its photograms; is not the stereotype of a fixed image, a quotation to which our language is glued? And in the common-place have we not a dual relation: narcissistic and maternal?

***

How to come unglued from the mirror? I’ll risk a pun to answer: by taking off (in the aeronautical and narcotic sense of the term). Of course, it is still possible to conceive of an art which will break the dual circle, the fascination of film, and loosen the glue, the hypnosis of the lifelike (of the analogical), by some recourse to the spectator’s critical vision (or listening); is this not what the Brechtian alienation-effect involves? Many things can help us to “come out of” (imaginary and/or ideological) hypnosis: the very methods of an epic art, the spectator’s culture or his ideological vigilance; contrary to classical hysteria, the image-repertoire vanishes once observes that it exists. But there is another way of going to the movies (besides being armed by the discourse of counter-ideology); by letting oneself be fascinated twice over, by the image and by its surroundings-as if I had two bodies at the same time: a narcissistic body which gazes, lost, into the engulfing mirror, and a perverse body, ready to fetishize not the image but precisely what exceeds it: the texture of the sound, the hall, the darkness, the obscure mass of the other bodies, the rays of light, entering the theater, leaving the hall; in short, in order to distance, in order to “take-off”, I complicate a “relation” by a “situation”. What I use to distance myself from the image-that, ultimately, is what fascinates me: I am hypnotized by a distance; and this distance is not critical (intellectual); it is, one might say, an amorous distance: would there be, in the cinema itself (and taking the word at its etymological suggestion) a possible bliss of discretion?”

How to come unglued from the mirror?

Roland Barthes

Translated from french by Richard Howard.